Jerusalem was destroyed twice, in 586 B.C.E. and 70 C.E. New archaeological work at Mount Zion reveals evidence of both horrors, a new theory for Nehemiah’s walls, rare weights from the First Temple period – and a magical rib bone

by Ruth Schuster

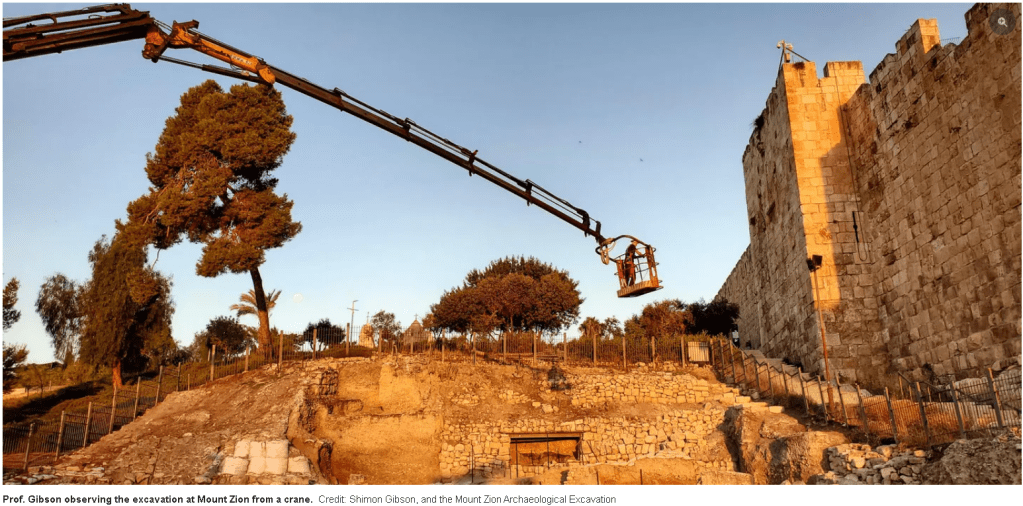

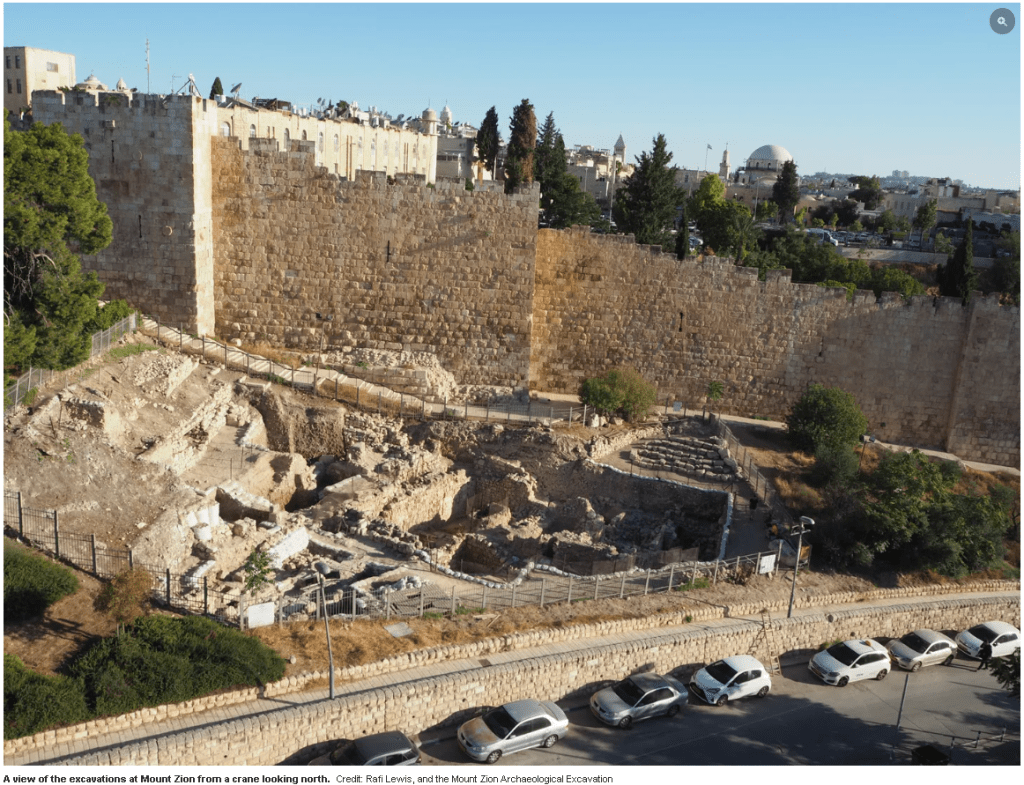

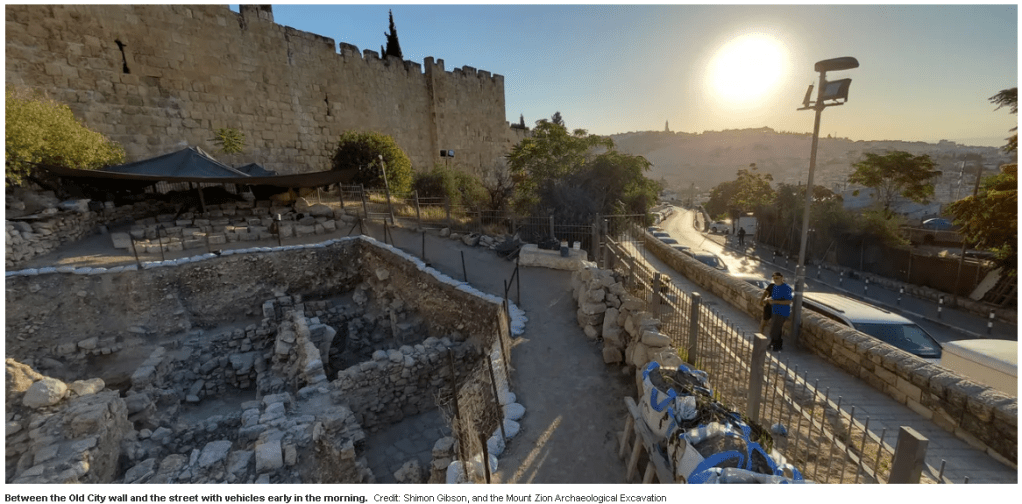

The eastern slope of traditional Mount Zion is the scene of an archaeological conundrum. A densely layered site is visible nestling between the traffic-choked road snaking around the Old City of Jerusalem and in front of the southern Ottoman Old City wall. To the sound of constant honking, church bells, pilgrims singing and muezzin prayers, the archaeologists have been unearthing a crazy matrix of disrupted archaeological layers going back many thousands of years.

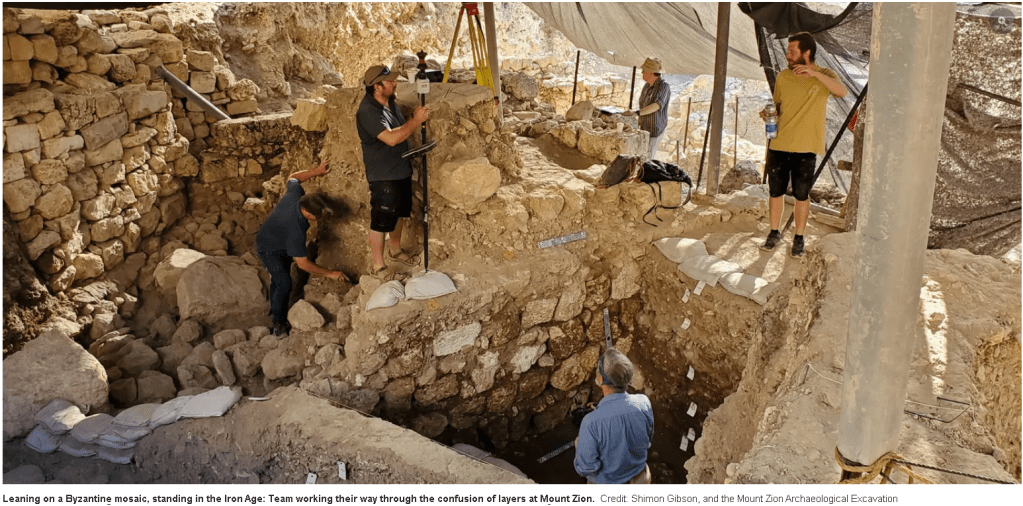

Mount Zion might be considered a stratigraphic nightmare studded as it is with enough pottery pieces and small finds to sink a trireme. “Reverse stratigraphy” with chronological layers out of order, is commonplace here. It’s enough to make any archaeologist shudder.

Pottery is usually useful for dating purposes. But here, for example, Iron Age pottery from the eighth to sixth centuries B.C.E. pops up in almost all the layers through to the Ottoman era, which is spectacularly unhelpful. A Roman layer emerges superimposed above a (later) Byzantine layer, which isn’t supposed to happen: they’re supposed to be the other way around.

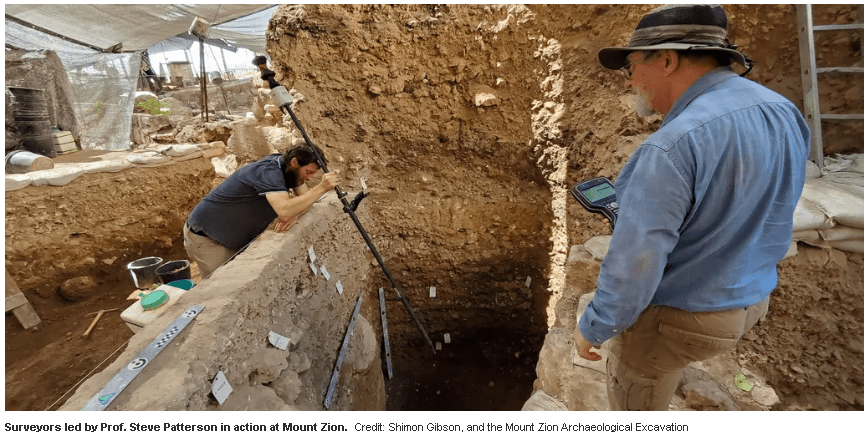

Puzzling out the intricacies on Mount Zion is an international archaeological team led by Prof. Shimon Gibson of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte with Dr. Rafi Lewis, a senior lecturer at Ashkelon Academic College and fellow at the University of Haifa. Deep pits are being dug; every small layer of sediment or change in the soil is documented. Staffers run around, taking measurements and documenting finds; labels are stuck in the sides of trenches marking all perceived changes. All extracted soil is washed in flowing water to ensure that all finds, however small, are collected.

One sure thing: They have found evidence of the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in the year 70 and, a couple of meters below that, the destruction of the First Temple and city by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.E. It is the first time that both destructions are documented in the same space.

In its lifetime, Jerusalem has seen much conflict. In addition to having being utterly destroyed twice, it was also besieged 23 times, attacked 52 times, and captured or recaptured 44 times, according to Prof. Eric Cline of George Washington University, author of “Jerusalem Besieged” (2004). But this site on Mount Zion is the only place (so far) where signs of both conflagrations have been found in close proximity, in layers situated one above the other, the archaeologists say.

Among the evidence of the 586 B.C.E. attack by the Babylonians are bronze and iron arrowheads, and a piece of jewelry – probably an earring – made out of gold and silver. Nobody would just drop that and walk on; its abandonment may attest to the panic that ensued during the Babylonian attack, says Gibson.

From the Roman attack in the year 70, the team has unearthed collapsed walls with stones calcified by the intense heat of the flames when the houses were put to the torch, causing upper floors to collapse – resulting in scattered, broken frescoes.

The scenes of devastation are quite moving, Gibson says. And among the stones was a small, unique find: a rib bone inscribed with drawings and Hebrew letters. It was presumably an amulet, possibly wielded to ward off Roman invaders. If so, it clearly didn’t work.

See foundation, will steal

As Haaretz arrived for the last day of the summer 2023 excavation season, the team was excavating floors from the Iron Age, from the seventh or early sixth centuries B.C.E.

Why is interpreting the story of Mount Zion in southern Jerusalem such a head-scratcher? Because in a classic tell, new settlements arose atop old ones and the lowest layer will inevitably be the earliest. At Tell Megiddo, for instance, archaeologists found orderly layers of settlements from the Early Bronze Age until the town’s destruction in the Iron Age. This is what archaeologists like.

Such neatness isn’t the case anywhere in Jerusalem, Gibson says. Pointing to a certain spot, he says: “Over there we found a late Byzantine layer which is above an early Roman layer which is above an early Byzantine layer, which is totally illogical.” It’s also an empirical fact, though, based on dating largely relying upon on coinage and pottery styles.

So, how did such stratigraphic mayhem arise?

“Urban architectural landscaping,” Gibson explains. “Today, landscaping is done with bulldozers, cutting into the ground and reshaping it. Back then, they did it by back-breaking human effort, using simple tools and shifting soil and rubble around with wagons, redepositing and moving building stones around, digging down to establish firm foundations for buildings, robbing stones from walls and cutting through earlier strata. In this chaos, an archaeologist has to uncover the layers very carefully, or chronological mistakes can occur.

“You have to understand the mechanism of a messed-up stratigraphy, with a balagan [confusion] of layers, deep cuts, robber trenches and ghost walls – otherwise you can easily lose the plot,” he says.

Also, Jerusalem has been undergoing archaeological investigation for more than 150 years. Mount Zion itself had been investigated before, including by Kathleen Kenyon back in the 1960s and Magen Broshi in the ’70s. The debris left behind by earlier digs has been another source of confusion.

“When you have this kind of complexity, it perfectly reflects the chaotic historical Jerusalem that this city has always been about. Nothing is straightforward, and we have to constantly think outside the box,” the professor sums up, based on decades of experience excavating in the city (including more than two decades at this specific site).

Asked how long this part of Mount Zion was actually inhabited, Gibson answers: at least from the Iron Age, some 3,000 years ago, until 1926.

It was? “Indeed, there was a kindergarten established just above the site by American benefactors in the ’20s,” he explains – a multicultural one that was designed for Muslim, Christian and Jewish toddlers to try to understand each other and their differences.

Shekel weights and the 0.1 percent

The First Temple has never been found and neither has the Second, but there is historical evidence for both. However, excavations have been revealing what Iron Age domestic life was like.

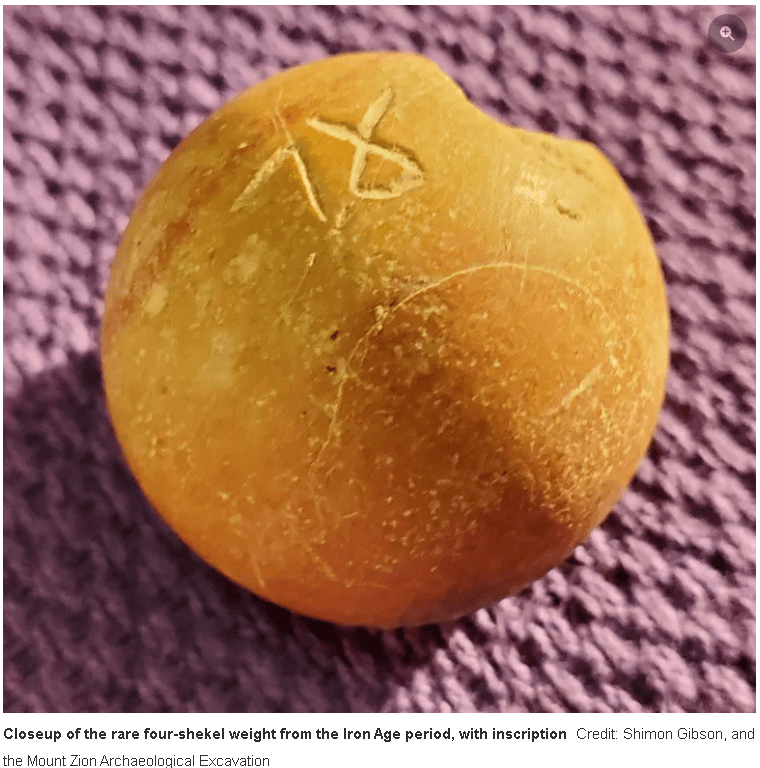

Among the most precious finds in the Mount Zion dig of 2023 was a rare, inscribed 4-shekel weight. It is in exquisite condition except for a ding on one side. Domed in shape and made of polished pink limestone, it was unearthed by Philip Nadela, a volunteer from the Philippines who is also part of a group helping to fund the dig.

A second, whiter and slightly more time-beaten inscribed half-shekel domed weight, a beka, appeared just as the season was wrapping up.

Both were found as the team carefully uncovered the Iron Age layer at this spot for the first time, revealing the floors of the ancient structures.

Why did it take so long to reach the Iron Age layer if this spot has been dug for decades, and given that Iron Age pottery was identified in every layer from the first?

When Kenyon observed Iron Age pottery on Mount Zion back in the ’60s , she assumed it had been “imported” there with soil as landfill from elsewhere, Gibson explains. Kenyon was a minimalist in terms of the extent of the Iron Age city, assuming it didn’t encompass Mount Zion of today within its walls.

“Of course, Kenyon’s notions are unsustainable. You would have to envisage Iron Age people from the ‘City of David’ hauling up bags of potsherds to Mount Zion simply in order to distribute them on the ground, and thus to annoy archaeologists 3,000 years later – the whole notion is quite absurd,” he says.

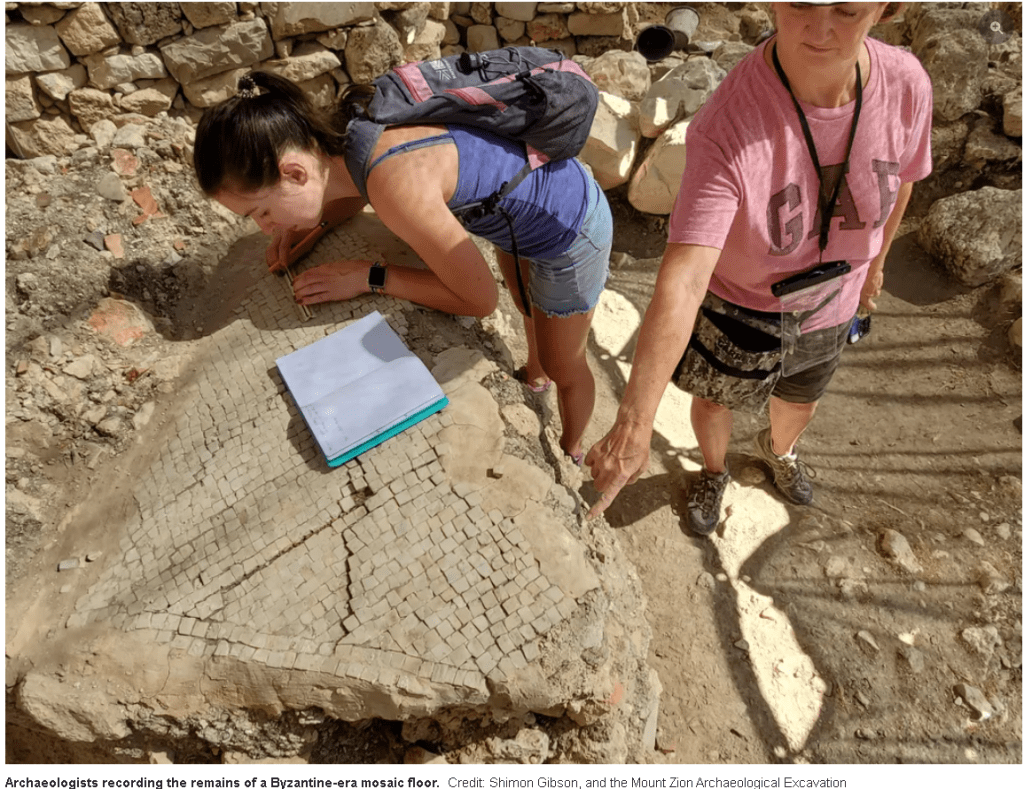

So Kenyon didn’t look for Iron Age structures there, it seems, but mainly, the seeming snail’s pace of the dig’s progress over decades is due to the sheer complexity and density of its structural layers: Byzantine houses above first-century chambers that are located well below the level of the Byzantine street (a modest southern continuation of the main Cardo Maximus street that traversed Byzantine Jerusalem); in between there are layers of debris from the Herodian period. A Byzantine sandwich containing a Roman filling, which is not at all straightforward – and not at all what archaeologists like digging.

The only option is to excavate the hundreds and thousands of levels, surfaces and sediments diligently, testing everything as they go along, constantly recording and documenting.

“Sometimes, together with Gretchen Cotter, who is in charge of the dig headquarters, I’ll go through hundreds of potsherds from a given fill, to find that 99.9 percent of it is of Roman date with 0.1 percent of Byzantine date – and it’s the latter that will actually date the deposit, unless there is some evidence of later intrusive activity in the layer,” Gibson says.

Dating is facilitated by coinage, found with the help of the expedition’s top-notch metal detector, he explains.

Hence, the team was able to deduce the chronological identity of a stone street by dint of removing the covering paving stones and finding beneath them a Greek-inscribed pottery sherd and eight coins. The accompanying pottery was from the late Byzantine period – probably built at the time of Justinian in the mid-sixth century, when heavy landscaping was being carried out in the area at the time of the construction of the massive Nea Church to the north of the site, Gibson says.

While building the street, the Byzantine construction workers poured tons of fill containing Iron Age and Roman-era material before laying down the foundations of the street itself, the team posits. What a mess.

Heartbreak of an Iron Age cauldron

“The remnant [of Jews] that are left of the captivity there in the province are in great affliction and reproach; the wall of Jerusalem also is broken down, and the gates thereof are burned with fire” – Nehemiah 1:3

Nehemiah wept upon hearing that account, according to the biblical narrative. He admitted that the Jews had erred and sinned, and beseeched the deity for help, and thus, reportedly, obtained the Persian overlords’ blessing to return from exile in Shushan and to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem in the fifth century B.C.E.

The question is which walls he restored. The assumption has always been that the walls around the “City of David,” south of Temple Mount, are the ones referred to in Nehemiah.

“Based on results of the Mount Zion excavations, I would say this is incorrect,” Gibson says. Quite a lot of pottery from the time of the Achaemenids (539-332 B.C.E.) has been found on traditional Mount Zion. In fact, it would seem Nehemiah restored parts of the original Iron Age wall and gates associated with Mount Zion, not just at the City of David, the archaeologist avers.

“When the Hasmoneans came to rebuild Jerusalem in around 140 B.C.E., after the Maccabean Revolt, they undertook similar building activities as Nehemiah. They rebuilt the original Iron Age wall, with the Persian-period restorations as well. Thus, the memory of the city destroyed by the Babylonians was preserved by the Hasmoneans,” he adds.

At the core of the site, beneath levels of walls and fills of rubble, the archaeologists have identified an intact mikveh (ritual purification bath) and, behind it, a secret chamber where Jews might hide from the Romans.

Elsewhere in the site, within the Iron Age levels, the team uncovered a large, cracked ceramic cauldron. Much maneuvering ensued by the conservator to try and extract the pot intact, but it was not to be. The moment they tried to lift it out, it crumbled.

Another intriguing find that day was a divination knucklebone dating to the late Byzantine to early Islamic periods, between the sixth to 11th centuries, which co-director Lewis points out attests to the multicultural character of late antique Jerusalem – which included not just Jews, Muslims and Christians (though these are known to have dabbled in divination as well).

And wow … what a site. At any given moment, one can stand with one foot in an Islamic period layer, the other resting on a floor from the Iron Age, your sweat dripping down on Roman remains. And if you were to bend down, you would find yourself examining an arrowhead from an ashy layer within the Muslim Fatimid moat, marking a point in time when an ungrateful young Crusader decided to rebel against his mother, the queen of Jerusalem.

Game of Crusader thrones

Actually, the archaeological finds from Mount Zion relating to Crusaders belong to two different bloody interludes, Lewis says. The first involved the conquest of Jerusalem from the Muslim Fatimids, in mid-1099, at the time of the First Crusade.

The Crusaders attacked Jerusalem from north and south. But the campaign at Mount Zion on the city’s south side, led by the famed Raymond of Saint-Gilles, did not go well.

“According to the sources, he managed to build a siege tower on the summit of Mount Zion but encountered a ditch-like dry moat between him and the city,” Lewis explains. That moat had been dug through the soil and rubble at the base of the wall by the Islamic forces to keep the Crusaders at bay, he adds.

“Count Raymond offered one dinar for every three stones brought to fill up the moat, so he could bring the siege tower successfully against the southern city wall,” adds Lewis. Well, they did fill the moat and bring the siege tower to the walls, only to have the city’s defenders immediately burn the thing down. However, next morning, the other barons breached the walls from Jerusalem’s north and ultimately the whole city was taken.

Somehow, Raymond managed to be the first Crusader to reach the Citadel, which they referred to as the “Tower of David” (which had no association with the fabled biblical king – it was actually built by King Herod), Lewis relates. The Crusaders then went on to massacre everybody during a four-day rampage, with one exception. The people sheltering in the citadel, Jews, Muslims and Christians, survived. “Raymond negotiated with them,” Lewis says simply.

Finds from this episode include the filled-in ditch-like moat, as well as arrowheads and cross pendants – including a bronze one that the team deduced, with the assistance of Israel Police forensic experts – showed damage caused by a swinging sword.

The second episode of Crusader violence detected on Mount Zion was when King Baldwin III, ruler of the Galilee, felt hard done by.

“He was an arrogant youth,” says Lewis. The word unfilial also comes to mind. Anyway, in the mid-12th century, this king of the Galilee rebelled against his mother Melisende, the noted queen of Jerusalem.

Melisende was the daughter of Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem. In about 1129, she had been forced to marry a French nobleman, Fulk of Anjou and Maine. Upon Baldwin II’s death, Fulk and Melisende became king and queen of Jerusalem. “Their relationship was not good,” says Lewis, apparently understating the case. Yet they had two sons and, to make a convoluted story short, Melisende gained the upper hand over her scheming, envious husband and became the queen regnant, not merely a regent in the name of the next male heir, Baldwin III.

Displeased with this arrangement, the young Baldwin III ultimately eventually led an army from the Galilee to Jerusalem, squatted on Mount Zion – then outside the city walls – and besieged it for 10 days, Lewis explains. Ultimately, they came to terms and Baldwin III became king of Jerusalem, leaving behind a thick layer of ash replete with arrowheads and other evidence of fighting.

This evidence was sealed by the next debacles du jour between the Crusaders and Ayyubid forces. Among other developments, upon learning that Jerusalem had been potentially offered (on a temporary basis) to the Crusaders as part of a bigger deal, the city’s Ayyubid ruler of that time had the city walls torn down in 1219 and 1227 – so at least the devils wouldn’t get a fortified city, Lewis explains.

It is these large ashlars and voussoirs from the gate tower demolished at that time that form the upper layer of the Mount Zion excavation today, says Lewis, who has personally been working on the dig for almost 24 years, with a seven-year break for the first intifada.

In the early 13th century, this neighborhood was replaced with a fish market with a sideline in chicken eggs. “In the layers of the marketplace we excavated, there were large quantities of chicken eggshells and fish bones,” Lewis recounts. “In the 2014 season, we even found a fish hook” – not to catch the creatures, since Jerusalem has no water other than the fish-free Gihon Spring. The hook was used to hang the fish from the shop or stall beams. The market ceased functioning when the city fortifications were destroyed in 1219.

Beneath the Ayyubid marketplace is burnt ash layer from the conflict between Melisende and her son Baldwin III. Beneath that is the irregularly cut Fatimid moat that held up the Crusader conquest of Jerusalem in 1099. Further down, more houses and a street from the Byzantine and Islamic periods, and, even deeper, well-preserved barrel-vaulted chambers and burnt houses from the year 70. Then, of course, there are the houses destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.E.

And what lies beneath the First Temple destruction layer, one wonders? Could there be remains from prehistoric and proto-historic times? Only time will tell. To date, the only find from the city’s very early beginnings in the Neolithic period is one solitary arrowhead, small but deadly, which could serve as a symbol of things to come in Jerusalem’s bloody future.

Originally published in Haaretz: Evidence of Jerusalem’s Destruction at the Hands of Babylonians, Then Romans Now Revealed on Mount Zion